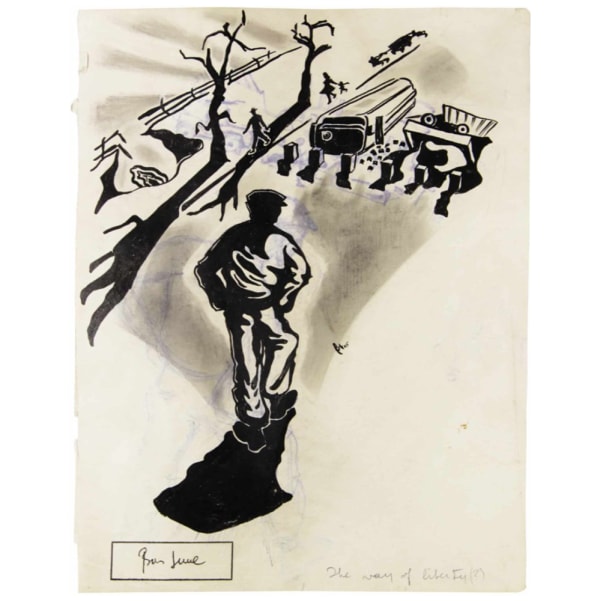

Boris Lurie American, 1924-2008

Boris Lurie was born 1924 in Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg), Russia, and grew up in Riga, Latvia. At the age of sixteen he was taken prisoner by the Nazis and imprisoned for a period of four years at Buchenwald and other concentration camps. After his liberation Lurie remained in Germany for a year and worked for the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps. He moved to New York City in 1946 and began his art career there. From 1954 to 1955 he lived and worked in Paris.

Boris Lurie first gained national attention in 1960. During this year he, along with Sam Goodman and Stanley Fisher, created the NO!art movement. The principle aim of NO!art was to bring back into art the subjects of real life. It thus stood in opposition to the two most popular movements of the era, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art.

For the most part critics and curators of the day rejected Lurie and NO!art. As he has stated, “The art market is nothing but a racket. There is an established pyramid which everybody who wants to benefit from it has to participate—if he is permitted to participate.” Yet Lurie continued to produce his highly charged political and social imagery and, in 1963, his now famous collage, Railroad Collage—which superimposed a pin-up girl in front of victims of a concentration camp—caused a major furor.

He died in 2008 in New York. Boris is buried in Hof Hacarmel cemetery in Haifa, Israel.

-

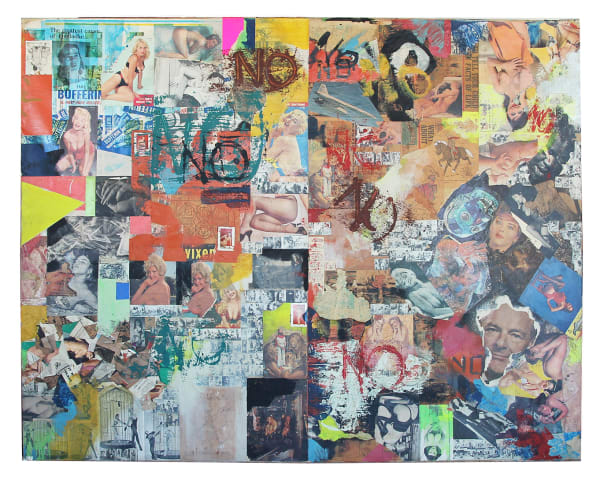

Big NO Painting, 1963

Big NO Painting, 1963 -

NO with Pinups and Shadow (Large NO Painting), 1958

NO with Pinups and Shadow (Large NO Painting), 1958 -

Torn Pinups, 1962-1963

Torn Pinups, 1962-1963 -

Untitled (Torn Pinups), circa 1962

Untitled (Torn Pinups), circa 1962 -

Untitled (Suzy Sweet), 1963

Untitled (Suzy Sweet), 1963 -

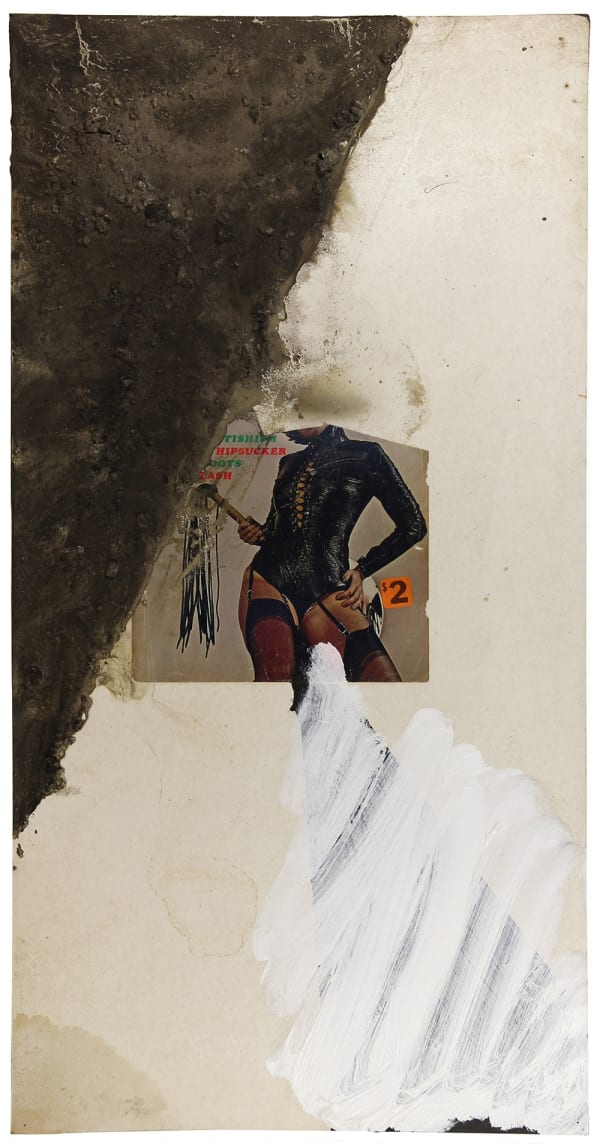

Untitled (Deliberate Pinup), circa 1975

Untitled (Deliberate Pinup), circa 1975 -

Untitled (Deliberate pinup series), circa 1975

Untitled (Deliberate pinup series), circa 1975 -

PISS, circa 1973

PISS, circa 1973 -

IN, circa 1973

IN, circa 1973 -

NO Poster, 1963

NO Poster, 1963 -

NO poster Overpainted, 1963

NO poster Overpainted, 1963 -

NO Posters Mounted, 1963

NO Posters Mounted, 1963 -

Relief: Stripper with NOs, 1958-62

Relief: Stripper with NOs, 1958-62 -

NO on Plastic, 1966-69

NO on Plastic, 1966-69 -

NO Record, 1962

NO Record, 1962 -

Feeling Painting NO with Red and Black, 1963

Feeling Painting NO with Red and Black, 1963 -

NO Stencil, 1963

NO Stencil, 1963 -

Dismembered Woman, circa 1955

Dismembered Woman, circa 1955 -

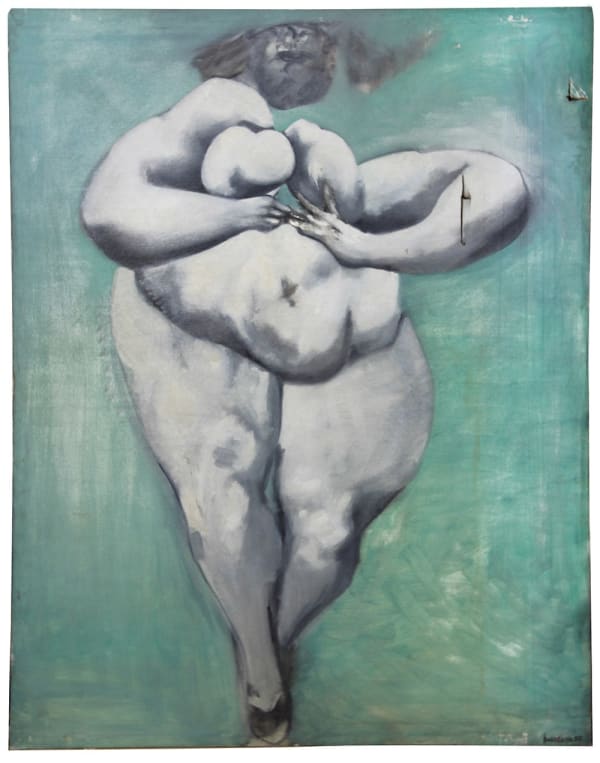

Dismembered Woman: Nude, Stepping, circa 1955

Dismembered Woman: Nude, Stepping, circa 1955 -

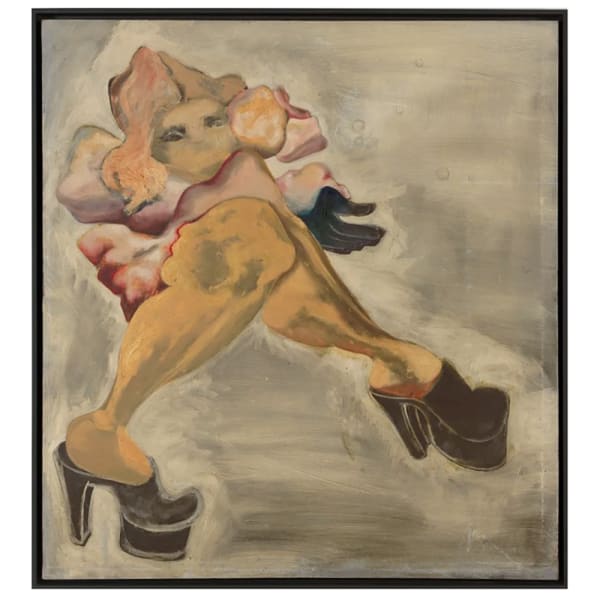

Dismembered Woman: The Stripper, 1955

Dismembered Woman: The Stripper, 1955 -

Altered Photos: Pinup (Dismembered figure), circa 1963

Altered Photos: Pinup (Dismembered figure), circa 1963 -

Untitled (Three Women #1), 1958-59

Untitled (Three Women #1), 1958-59 -

Untitled (Three Women), 1957

Untitled (Three Women), 1957 -

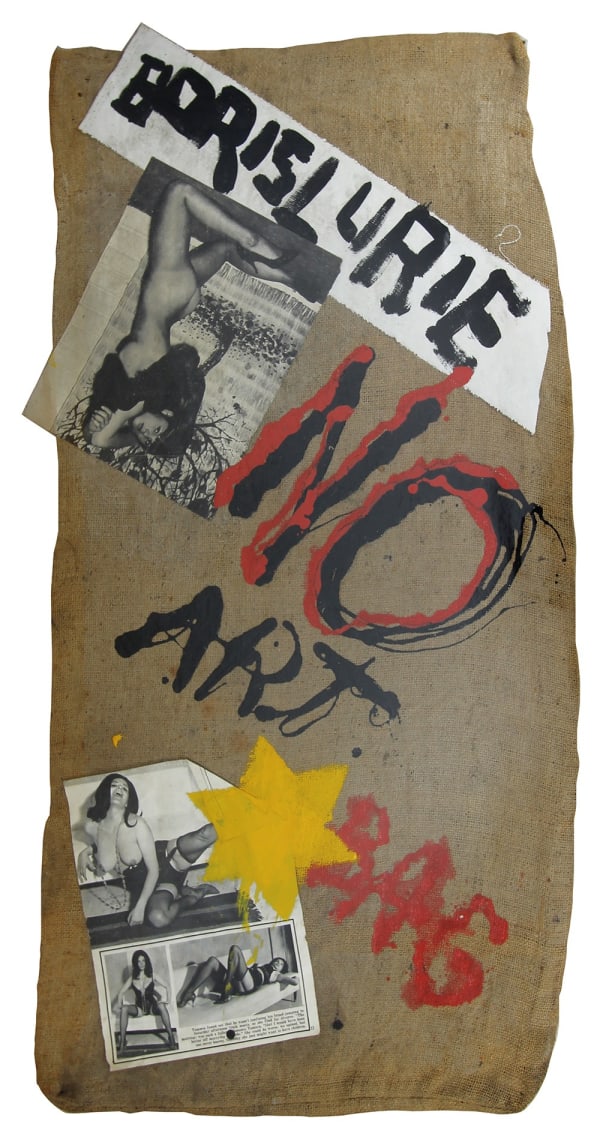

NO!art Bag, 1974

NO!art Bag, 1974 -

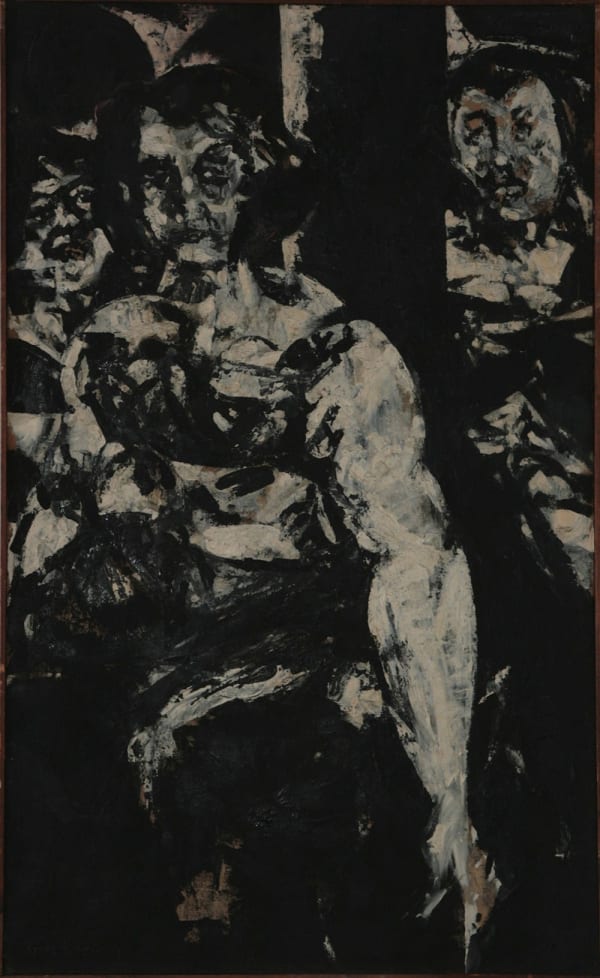

Untitled, 1958

Untitled, 1958 -

Untitled, 1956

Untitled, 1956 -

NO on Reversed Pinups, 1971-72

NO on Reversed Pinups, 1971-72 -

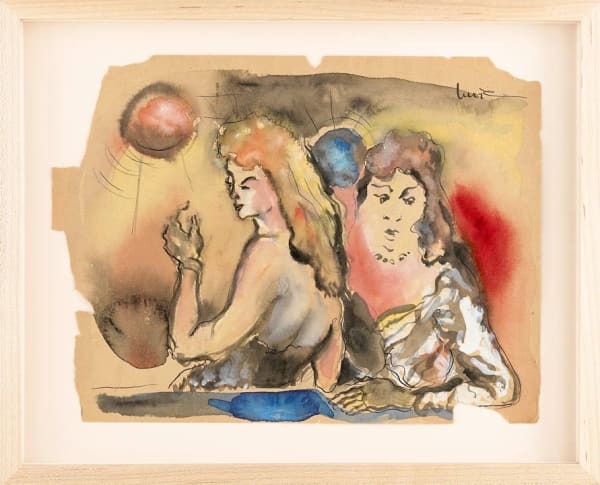

Untitled, 1950

Untitled, 1950

-

Westwood Gallery NYC: 30 Years

6 Sep - 25 Oct 2025In celebration of WESTWOOD GALLERY NYC's 30th Anniversary, the gallery will present a group show highlighting works from artists across our three decade history alongside installation views of past exhibitions.Read more -

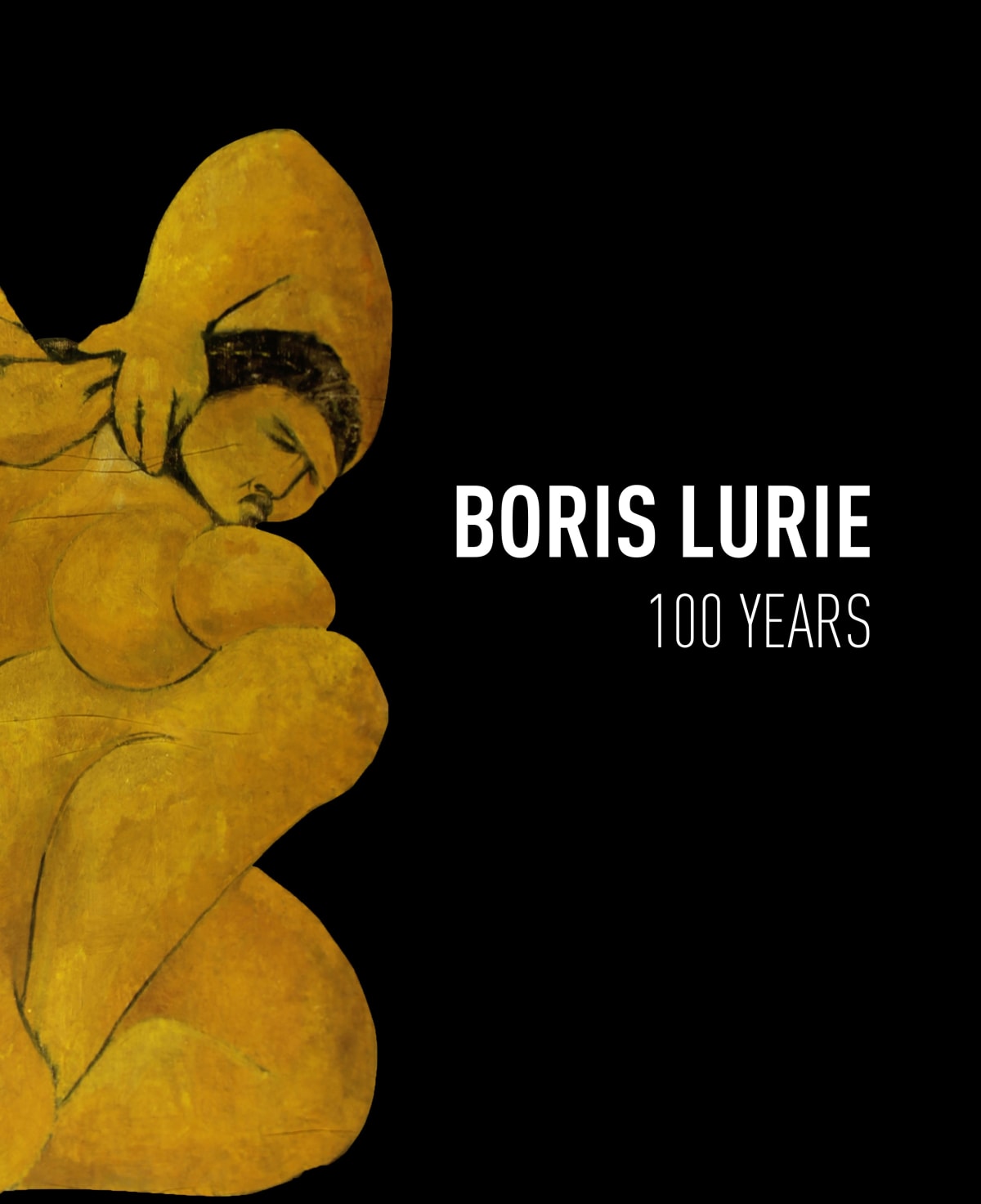

Boris Lurie: 100 Years

18 - 27 Jul 2024Westwood Gallery NYC , in collaboration with the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, presents Boris Lurie: 100 Years , a landmark exhibition honoring the centennial of the influential artist and co-founder...Read more -

Boris Lurie: Life After Death

3 Jan - 18 Feb 2017Boris Lurie: Life After Death presented an exhibition of paintings, collage, and sculpture by Boris Lurie, the founder of the NO!Art movement, in conjunction with the Boris Lurie Art Foundation.Read more -

Boris Lurie: NO!ART, Early Work

4 Jun - 31 Jul 2010Boris Lurie: NO!ART presented an exhibition of paintings, drawings, collage and sculpture by Boris Lurie (1924-2008), the first exhibition since the artist's death.Read more

2021 - Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But To Try, Museum of Jewish Heritage - A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, New York, NY

2021 - Downtown Train, PS122 Gallery, New York, Sep 9 - Oct 3

2021 - Stop Painting, Prada Foundation, Venice, May 22 - Nov 21

2021 - Boris Lurie, Das Haus von Anita, Center for Persecuted Arts, Solingen, Germany, May 8 - Aug 1

2021 - Boris Lurie: In Riga, Žanis Lipke Memorial, Riga Latvia, Mar 4, 2021 - Jul 31

2020 - Boris Lurie in America: He had the courage to say NO!, The Center for Contemporary Political Art, Washington, DC, Jan 26 - Apr 26

2019 - Shit and Doom - NO!art, Cell Project Space, London, Sep 19 - Nov 3

2019 - Altered Man - The Art of Boris Lurie, Kyiv National Art Gallery, Shokoladnyi Budynok Art Center, Kyiv, Ukraine, Sep 6 - Oct 30; traveled to Odesa Fine Arts Museum, Odessa, Ukraine, Nov 15, 2019 - Jan 15, 2020

2019 - Portable Landscapes: Memories and Imaginaries of Refugee Modernism, The James Gallery, The Graduate Center, CUNY, New York, Nov 19, 2019 - Feb 15, 2020

2019 - It is the Sunlight That Warms the Room (Es el sol que calienta la habitación), Museo Vostell Malpartida, Cáceres, Spain, Sep 1, 2019 - Mar 31, 2020

2019 - Boris Lurie. American Nonconformist, The State Russian Museum / The Stroganov Palace, St Petersburg, Russia, Aug 29 - Nov 11

2019 - Confrontation NO!art Group, Janco-Dada Museum, Ein Hod, Israel, Jul 20 - Nov 30

2019 - Boris Lurie: Artist and Witness, Mark Rothko Art Centre, Daugavpils, Latvia, Apr 26 - Jun 23

2019 - Boris Lurie and NO!art Group, Koroška Art Gallery, Slovenj Gradec, Slovenia, Apr 5 - Jun 2

2019 - Forgetting - Why We Don't Remember Everything, Historisches Museum Frankfurt, Germany, Mar 6 - Jul 14

2019 - NO!art Exhibition, The Riga Bourse (Latvian National Museum Of Art), Rīga, Latvia, Jan 11 - Mar 10

2018 - Boris Lurie: Pop-art After the Holocaust – MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art In Krakow, Poland

2018 - Flashes of the Future: The Art of the ’68ers or The Power of the Powerless Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kuns, Aachen, Germany

2017 - You’ve Got 1243 Unread Messages. – Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga, Latvia

2017 - Boris Lurie in Habana – Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba

2017 - Boris Lurie. Anti-Pop - Neues Museum Staatliches Museum für Kunst und Design Nürnberg, Germany

2017 - Boris Lurie: Life After Death, Westwood Gallery NYC, Jan-Feb

2017 - Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 – Grey Art Gallery, NYU, New York NY

2016 - Boris Lurie. Adieu Amérique – CAMERA - Centro Italiano per la Fotografia, Torino, Italy

2016 - BORIS LURIE NO! – Janco Dada Museum, Ein Hod, Israel

2016 - No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie – Jewish Museum Berlin

2015 - Unorthodox – Jewish Museum, New York NY

2015 - Boris Lurie NO!art – Galerie Odile Ouizeman, Paris, France

2014 - KZ – KAMPF – KUNST. Boris Lurie: NO!art NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln, Germany

2014 - Dessinez Eros (Group Exhibition) Galerie Odile Ouizeman, Paris, France

2014 - El Museo Vostell Malpartida, Spain.

2014 - The Box LA, Stand A14, Frieze Art Fair – New York. NYTimes.com mentio

2013 - Boris Lurie, 1924–2008 – Charles Krause/ Reporting Fine Art, (e)merge art fair – Washington, DC

2013 - Art Against Art: Yesterday and Today – Zverev Center of Contemporary Art, Moscow

2013 - Boris Lurie, The 1940s, Paintings and Drawings – Studio House, New York NY

2013 - NO!art: The Three Prophets – The BOX, Los Angeles, CA

2012 - A Self To Recover: Embodying Sylvia Plath's Ariel – Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN

2012 - Boris Lurie – David David Gallery

2012 - Boris Lurie: NO!art of the 1960s – Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights, Firenze, Italia

2011 - NO!art at the Barricades – Chelsea Art Museum, NYC

2011 - NO!art of Boris Lurie – Zverev Center for Contemporary Art in Moscow, Russia

2011 - NO! The Art of Boris Lurie at Chelsea Art Museum – Chelsea Art Museum, NYC

2011 - Atonement (Oratorio composed by Marvin David Levy dedicated to Boris Lurie and Holocaust victims), Temple Emanu-El

2011 - BORIS LURIE: NO!art – Pierre Menard Gallery, Cambridge, MA

2011 - Los Angeles Art Fair, Westwood Gallery Booth

2010 - Art|Miami, Westwood Gallery Booth

2010 - NO!art | An Exhibition of Early Work, Westwood Gallery, New York

2009 - On the Tectonics of History, ISCP, New York

2009 - ART FAIR 2009 – New York – Pierre Menard Gallery, Cambridge

2005 - The '80s, Clayton Gallery & Outlaw Art Museum, New York

2005 - Wild Boys, Dad Boys, Outsiders, and Originals | Clayton Gallery, New York

2004 - Feel Paintings / NO!art show #4, Janos Gat Gallery, New York

2003 - Optimistic – Disease – Facility, Boris Lurie – Buchenwald–New York, with Naomi T. Salmon at Haus am 2003 - Kleistpark, Berlin-Schoeneberg

2003 - NO!-ON – Gallery Berliner Kunstprojekt, Berlin

2002 - NO!art and the Aesthetics of Doom, Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City, IA

2001 - NO!art and the Aesthetics of Doom, Block Museum, Evanston, IL

1999 - Works 1946-1998, Weimar-Buchenwald Memorial, Weimar

1999 - Life - Terror - Mind, Show at Buchenwald Memorial, Weimar

1999 - Knives in Cement, South River Gallery (UIMA), Iowa City

1998 - NO!art Show #3 with Dietmar Kirves, Clayton Patterson & Wolf Vostell – Janos Gat Gallery, New York

1995 - NO!art, Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, Berlin

1995 - Boris Lurie und NO!art, Haus am Kleistpark, Berlin

1995 - Dance Hall Series, endart Gallery, Berlin

1995 - Holocaust In Latvia, Jewish Culture House, Riga

1994 - NO!art (with Isser Aronovici & Aldo Tambellini), Clayton Gallery, New York

1993 - Outlaw Art Show, Clayton Gallery, New York

1989 - Graffiti-Art – Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden

1988 - Feel-Paintings, Gallery and Edition Hundertmark, Cologne

1978 - Counterculturale Art (with Erro and Jean-Jacques Lebel), American Information Service, Paris

1975 - Recycling Exhibition, Israel Museum, Jerusalem

1974 - Boris Lurie at Inge Baecker, Inge Baecker Galerie, Bochum, Germany

1974 - NO!art Bags, Galerie und Edition Hundertmark, Köln

1974 - Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell, Galerie Rewelsky, Köln

1974 - NO!art with Sam Goodman & Marcel Janco, Ein-Hod-Museum, Ein-Hod, Israel

1973 - NO!art Painting Seit 1959, Galerie Ren é Block, Berlin; Galleria Giancarlo Bocchi, Milano

1970 - Art & Politics, Kunstverein Karlsruhe

1964 - NO & ANTI-POP Poster Show, Gallery Gertrude Stein, New York

1964 - Boxes, Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles

1963 - NO!show, Gallery Gertrude Stein, New York

1963 - Boris Lurie at Gallery Gertrude Stein, Gallery Gertrude Stein, New York

1962 - Sam Goodman & Boris Lurie, Galleria Arturo Schwarz, Milano

1962 - Doom Show, Galleria La Salita, Roma

1961 - Pinup Multiplications, D’Arcy Galleries, New York

1961 - Involvement Show, March Gallery, New York

1961 - Doom Show, March Gallery, New York

1960 - Dance Hall Series, D’Arcy Galleries, New York

1960 - Adieu Amerique, Roland de Aenlle Gallery, New York

1960 - Les Lions, March Gallery, New York

1960 - Tenth Street New York Cooperative, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1960 - Vulgar Show, March Gallery, New York; Joe Marino’s Atelier, New York

1960 - Joe Marino's Atelier, New York

1959 - Drawings USA, Museum of Modern Art, New York

1959 - 10th Street, Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston

1958 - Black Figures, March Gallery, New York

1951 - Dismembered Figures, Barbizon Plaza Galleries, New York

1950 - Boris Lurie, Creative Gallery, New York

-

Westwood Gallery, On Manhattan's Bowery, Marks Its 30th Anniversary

Exhibition ReviewJane Levere, Forbes, 31 Oct 2025 -

There Are a Ton of Shows to See Around the Venice Biennale

Boris Lurie: Life with the Dead in VeniceArtnet News, 19 Apr 2024 -

The Museum of Jewish Heritage opens new exhibit that showcases Holocaust survivor

Boris Lurie painted and drew a series that depicted his experiences in the Holocaust.Jerusalem Post Staff, The Jerusalem Post, 21 Sep 2021 -

Boris Lurie at the Chelsea Art Museum

Frieze, 1 Oct 2011 -

The Resurrection Of Boris Lurie And The NO!art Movement

Boris Lurie's Perverse Pin-ups And The NO!art MovementLisa Paul Streitfeld, Huffington Post, 29 Jun 2011 -

First and Final Refusal

Resurrecting Boris Lurie, the Original NO!art ManEzra Glinter, Jewish Daily Forward, 14 Jul 2010 -

Boris Lurie’s NO!art retrospective at Westwood Gallery

Theresa Byrnes, Mirror.co.uk, 7 Jul 2010 -

Boris Lurie's Early Work at Westwood

Robert Shuster, Village Voice, 22 Jun 2010 -

Saying Yes to NO!

Boris Lurie leaves his fortune to a foundation that will support works reflecting his anticonsumerist stanceDouglas Century, ARTnews, 1 Apr 2010

-

Boris Lurie at the Neues Museum Nuremberg

Testimony: Boris Lurie & Jewish Artists from New York 26 Sep 2025Early work by Boris Lurie is featured in Testimony: Boris Lurie & Jewish Artists from New York at the Neues Museum Nuremberg through February 1,...Read more -

Boris Lurie at the Eskenazi Museum of Art

Remembrance and Renewal: American Artists and the Holocaust, 1940–1970 4 Sep 2025Artwork by Boris Lurie is featured in the ground-breaking exhibition Remembrance and Renewal: American Artists and the Holocaust 1940–1970 at the Eskenazi Museum of Art...Read more -

Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But Try

Exhibition at the Zekelman Holocaust Center 24 Jul 2025Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But To Try is currently on view at the Zekelman Holocaust Center through December 5. The exhibition showcases Lurie’s War...Read more -

Westwood Gallery NYC at the Dallas Art Fair 2025

Booth F12A 21 Jan 2025WESTWOOD GALLERY NYC is pleased to announce our debut participation in the 2025 Dallas Art Fair. Please visit us at Booth F12A in the Fashion Industry Gallery, Dallas, TX.Read more -

Boris Lurie in Venice

Life with the Dead at the Scuola Grande San Giovanni Evangelista di Venezia 20 Apr 2024Boris Lurie is spotlighted in a solo exhibition coinciding with the Venice Biennale at the Scuola Grande San Giovanni Evangelista di Venezio. The exhibition, Life...Read more -

Boris Lurie at Museu Judaico de São Paulo

Boris Lurie: Grief and Survival 5 Apr 2023Boris Lurie’s artwork was exhibit edin Boris Lurie: Grief and Survival at the Museu Judaico de São Paulo, Brazil. The exhibition, curated by Felipe Chaimovich...Read more -

Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell at Ludwig Museum, Budapest, Hungary

BORIS LURIE & WOLF VOSTELL: ART AFTER THE SHOAH 31 Mar 2023Artwork by Boris Lurie was on exhibit in Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell: Art After the Shoah at the Ludwig Museum in Budapest. The two-person...Read more -

Boris Lurie at Museo Nacional de las Culturas del Mundo, Mexico City

No Complaciente: Boris Lurie en Mexico 15 Dec 2022Boris Lurie’s artwork is on view in No Complaciente: Boris Lurie en Mexico at Museo Nacional de las Culturas del Mundo (National Museum of World...Read more -

Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell at Museum Kunsthaus Dahlem

Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell: Art After the Shoah 8 Jul 2022Boris Lurie’s artwork is on exhibit in Art after the Shoah at the Museum Kunsthaus Dahlem, Berlin, Germany. The two-person exhibition highlights his work together...Read more -

Boris Lurie at the Museum of Jewish Heritage

Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But Try 22 Oct 2021Boris Lurie's artwork is on exhibition in Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But Try at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, New York, NY. The exhibition,...Read more -

Boris Lurie at Fondazione Prada, Venice

Group Exhibition: Stop Painting, curated by Peter Fischli 22 May 2021Boris Lurie's artwork is on view in Stop Painting , curated by Peter Fischl, at the Fondazione Prada, Venice. The exhibition examined five radical ruptures...Read more -

Boris Lurie at the Chelsea Art Museum

The Resurrection of Boris Lurie and The NO!Art Movement 26 Mar 2011The Chelsea Art Museum hosts the first exhibition in New York of art from the Boris Lurie estate. The show inaugurated a series of exhibitions...Read more